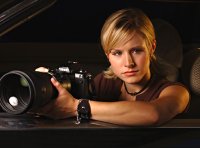

Veronica Mars

Warning: Spoilers Within.

I want to talk about Veronica Mars. Actually, I want to talk about it, write about it, watch it over and over. It’s a televisual addiction of mine, and I am not apologetic. A drama centered around a misanthropic teenage private eye is not the kind of show that inspires confessions of love on spec, but it has earned my love, and I will not deny it.

I was initially skeptical of Veronica Mars. I mean, after Buffy the Vampire Slayer, how many shows about smart, sassy teenagers does this world need? Apparently, one more. Apparently, the template is good for another series that uses the maligned teenager as a lightening rod for human emotion, foible, and triumph. I was skeptical. I turned up my nose. I was wrong.

As Buffy’s appeal was in its metaphors, Veronica Mars’s appeal is in extremes. Ironically, they make it believable. No, no-one I know was ever on trial for murder after handling a break-up poorly. But everyone I know has felt like they were on trial for murder after handling a break-up poorly. I don’t know anyone whose mother committed suicide and father was sent to jail in high school, but I did know a lot of teenagers who felt completely abandoned by selfish parents and circumstances beyond their control. And really, when you’re in the grip of extreme emotions, you often wish that there were extreme circumstances to justify them. You want proof that you have a right to feel like you just might die. Veronica Mars gives its characters extreme external circumstances in order to make clear just how extreme the emotions of betrayal, neglect, confusion, hate, love, lust really are, particularly when they are new to you. The result is carefully crafted, complicated characters that are completely identifiable. As Veronica says of Logan Echols (one of the most interesting, disturbing and—yes, I’ll say it—lovable characters on television) in the first episode, “Every school has its obligatory psychotic jackass.” And every school does. Maybe not literally, but we all know exactly who she means.

These complicated characters are enough to make a decent TV show. But what I may like most about Veronica Mars, other than its steadfast belief that brains, not fists, are the ultimate weapon and that weapon can be wielded by pocket-sized blonde girls, is its belief in the viewer and the rewards for those who watch it carefully. Veronica Mars regularly drops in plot developments in the tiniest increments, forcing you to be patient and accept that you do not understand what’s going on just yet. You see the trophy wife removing hair from a shower drain at the end of one episode and it’s hours of television until you hear that a murder weapon has been found carrying hair belonging to the character who showered above that drain. And no-one jumps up and down and screams, “Remember! Remember the hair! It was weird then, but it makes sense now! How about a flashback! Let’s look at her pick up that hair again, huh?” You either get it or you don’t. And when you get it, you feel pretty damn smug.

The mysteries in this series are sometimes very simple (Who forged those drug test results? Who stole the high school mascot?) but they are also often very complicated, and Veronica Mars doesn’t always get it right. She spent several episodes of season two tracking a lead that did not, and would not, lead her to the killer of a busload of high school students. (And even here, the discerning viewer is rewarded. As Veronica trails a member of local organized crime syndicate who mooned the high school students before the bus crashed, the episode is named “Nevermind the Buttocks.” The mooners are part of a red herring, and the audience understands that to be true long before Veronica will.) The final two episodes of season one are two of the finest hours of television I’ve seen in years, and in one of them she solves one of the season’s pressing mysteries. But she’s wrong. And you don’t know she’s wrong until the finale of season two. That’s right – you have to wait through 22 hours of television to find out that things were not as they appeared. It doesn’t sit right at the time, but you imagine that her initial solution is right. You assume that, once again, someone in television has imagined the end of a plotline in a way that isn’t quite satisfying. Not every show can be smart all the time. So you let it go, you figure it’s all so damn brilliant that one misstep can be forgiven. But you've been taken in; you’re the bad detective. Some television shows are that smart. Thank goodness. I watch a lot of TV. Shows like Veronica Mars justify the addiction.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home